Alastair Galpin

took to world record-breaking in

2004 after being inspired by a record-setting rally

driver in Kenya. What began as a hobby soon escalated

into an active publicity pursuit. Today, he promotes the

work of social and environmental causes. For these

purposes, the most fitting game plans are chosen; then

world titles are attempted and frequently created.

Sustaining sponsor

If you would like regular exposure from Alastair's activities, become his Sustaining Sponsor:

- A range of attempts annually

- Your brand in multiple media

- Distribute your own media releases

- Receive product endorsements

More details about sponsorship opportunities

Special thanks

|

Behind every world record attempt is the expertise of professionals in their field. Their success underpins Alastair's. |

| They are listed here |

Most radio interviews in suspended cage: 98

This is the story behind my world record for the Most radio interviews in a suspended cage.

Under normal circumstances, nobody would

volunteer to dangle from a crane in a caged public toilet over Easter.

If pressurised to do so, however, it'd be wise for the contender to

cope well with sea-sickness, not be scared of heights, and not have a

phobia of public toilets. But, as you probably know by now, I'm not

your average fellow. I can't hold my stomach for more than a few

minutes on a rocking boat, I don't like heights when I can avoid it,

and I'll do almost anything to avoid visiting a public toilet.

So why, one has to ask, would I be the one to

suggest this world record attempt? Because the opportunity arose, and I

wanted the attention for myself as well as for the social cause

associated: help for those affected by problem gambling. I thought it

was worth the effort, and I always will. Problem gamblers need to know

there's help.

It took approximately a year to set up this

event. There were tough times, like when the authorities would not let

plans progress without extensive hurdles being overcome. But the great

team of assistants I had overcame every challenge. Some of the planning

was fun too. It humoured many companies to hear of the plans and

think of ways to support it. Plans changed so many times to fit the

legal, safety and community aspects of the event, I wasn't always able

to keep up. In the end, we'd succeeded in arranging most things: a

portable public toilet that fitted into the man-cage for the crane, the

bare basics that anyone would need to live in a remote mountain hut

with, a computer for media contact, and an army of helpers to do just

about everything.

Finally, the big day in April came. The team

stuffed bags of belongings into the toilet and I slipped inside. After

some media attention and dozens of last-minute checks, I was secured

into my harness and the crane's engine hummed. Ooh! The cage began to

lift free of the ground and up I went as the wire rope spooled.

Initially, my heart was in my throat, but a few hours later I'd come to

terms with this: I'd either fall to my death or the Problem Gambling

Foundation of New Zealand would receive a great deal of media from my

being here.

Thankfully,

the

latter

happened.

I

spent

almost

all

day

and

night,

every

day

and

night,

seeking

radio

interviews.

I

picked

up

live

and recorded chats from right around New Zealand and to

the furthest corners of the world: the Falkland Islands, Tenerife,

Guam, the Inner Hebrides, Belize and more. I did try the main operating

channel in Antarctica, but perhaps that scientific community had other

priorities. Several Arctic outposts and smaller nations in the high

latitudes were a struggle to make arrangements with because I'm limited

to English. So, alas, I had to foresake the opportunity with keen

presenters in these regions.

Thankfully,

the

latter

happened.

I

spent

almost

all

day

and

night,

every

day

and

night,

seeking

radio

interviews.

I

picked

up

live

and recorded chats from right around New Zealand and to

the furthest corners of the world: the Falkland Islands, Tenerife,

Guam, the Inner Hebrides, Belize and more. I did try the main operating

channel in Antarctica, but perhaps that scientific community had other

priorities. Several Arctic outposts and smaller nations in the high

latitudes were a struggle to make arrangements with because I'm limited

to English. So, alas, I had to foresake the opportunity with keen

presenters in these regions.

Back in Britain, though, things were humming. I

was getting feedback regularly that locals were calling in, grateful to

radio show hosts highlighting the problem gambling issue. People spoke

of their loved ones being affected, the related crime and their fears

of family insecurity. A number of talk groups emerged on air, and even

a few regular talk back shows! I was called by a number of radio

stations, wanting more chatter on the issue. This continued for my

three-week escapade. The UK was highly receptive of the need to face

gambling addiction.

Australia loved the concept of a stunt to

highlight the situation. I was asked for so many interviews, I got to

recognise presenters' voices when they called. As in the UK, I was told

of stories involving Australians reaching out for help, and their

motivation to assist others as a result of our New Zealand project.

Canada responded with similar fervour. It was

here I had my longest interview during the attempt – 45 minutes live.

The national broadcaster duplicated a recorded interview I did with

them, and I heard from friends across the country's time zones that I

was under discussion on various programmes. Then a prominent Canadian

university used this event as part of a message aimed at youth,

alerting them to potential addictive behaviours.

The international media was having a feast. It

went on and on. Some radio stations interviewed me almost a dozen

times, I ended up on countless news and entertainment websites, large

and small newspapers wrote articles, television channels ran stories in

numerous countries and magazines published spreads of my work –

including this event - afterwards.

I was exhausted and filthy when I emerged after 3

weeks. Everyone who'd been involved was happy, though, for the

achievement we'd all created. We even created a slideshow to depict the

record

attempt, from which you can see the conditions I had endured.

Yet, my administrative duties were only

about to begin; all world record claims must be supported by exhaustive

paperwork. For the next year, I'd be collecting data of all sorts in

preparation to send to the judges. During this time, psychologists in a

handful of countries took a brief interest in how living in this

confined space had affected me. Friends also commented that since

emerging, I'd changed permanently to a slightly more subdued type. I

wonder what the full mental ramifications of this undertaking have been

on my mental state?

And would you believe it, one day, when

attempting another world record, I was approached by an individual. He

was clasping a newspaper clipping of me in this cage. I was puzzled as

he pointed to it inquiringly. Then he asked how he could beat my

achievement. I was encouraging to this potential challenger, but was

stunned that he had chosen this as his very first world record to

attempt. I've never heard from him since.

See the record slideshow

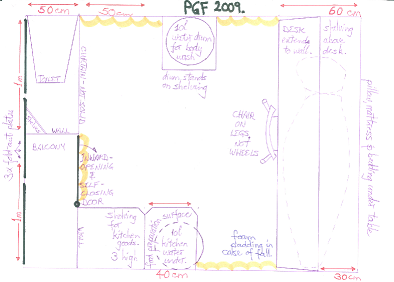

The diagram below was my sketch as to how to fit everything into the small space which was to be home for the event - it reflects just how tight a squeeze it was.